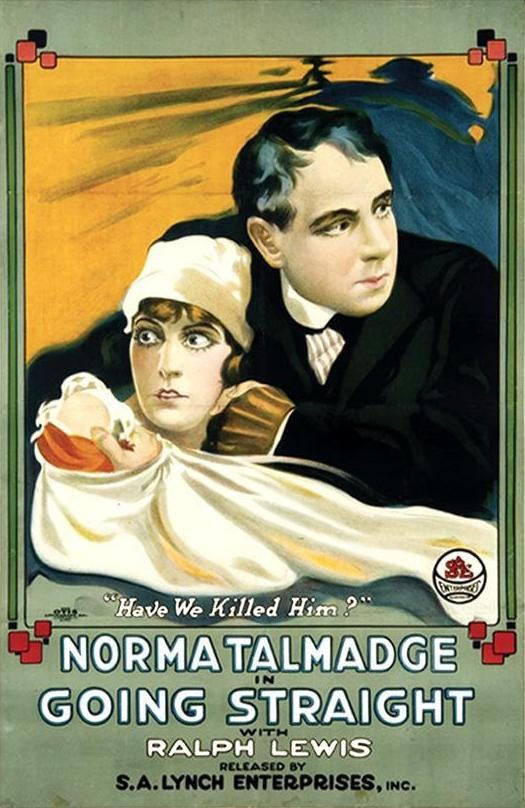

Between 1910 and 1915 Norma Talmadge was featured in over 100 short films for the Vitagraph Company, none of which I’ve had the chance to see. Yet, I recognize her name. Like so many stars of the silent film era, Talmadge endures as little more than a shadowy phantom of a bygone day, her name ringing a distant bell in the minds of film fans. We may have seen her name listed among other stars— Marguerite Clark, Theda Bara, Pearl White— all of whom were massively famous in their day, but relegated to footnotes, if that, today, or perhaps on a classic movie poster we’ve seen somewhere, but there the recognition ends. Despite being mostly forgotten today, between 1917 and 1926 Talmadge was probably the biggest female box office draw outside of Mary Pickford, and possibly Gloria Swanson. She was hugely famous in her day, bigger at her peak than even Garbo at hers, and Going Straight is my first chance to learn why.

In addition to watching Going Straight, I watched three of Talmadge’s Vitagraph shorts, Sawdust and Salome and A Helpful Sisterhood, both from 1914, and A Tale of Two Cities, from 1911. Had I known about them earlier, I’d have watched them when they came up in the chronology, but better late than never, right? In any event, they gave me a little bit more of a sense of who Talmadge was, though not much. Nothing about her jumped out at me and made me think “wow!” I wondered if Going Straight would give me better insight into why she was so famous.

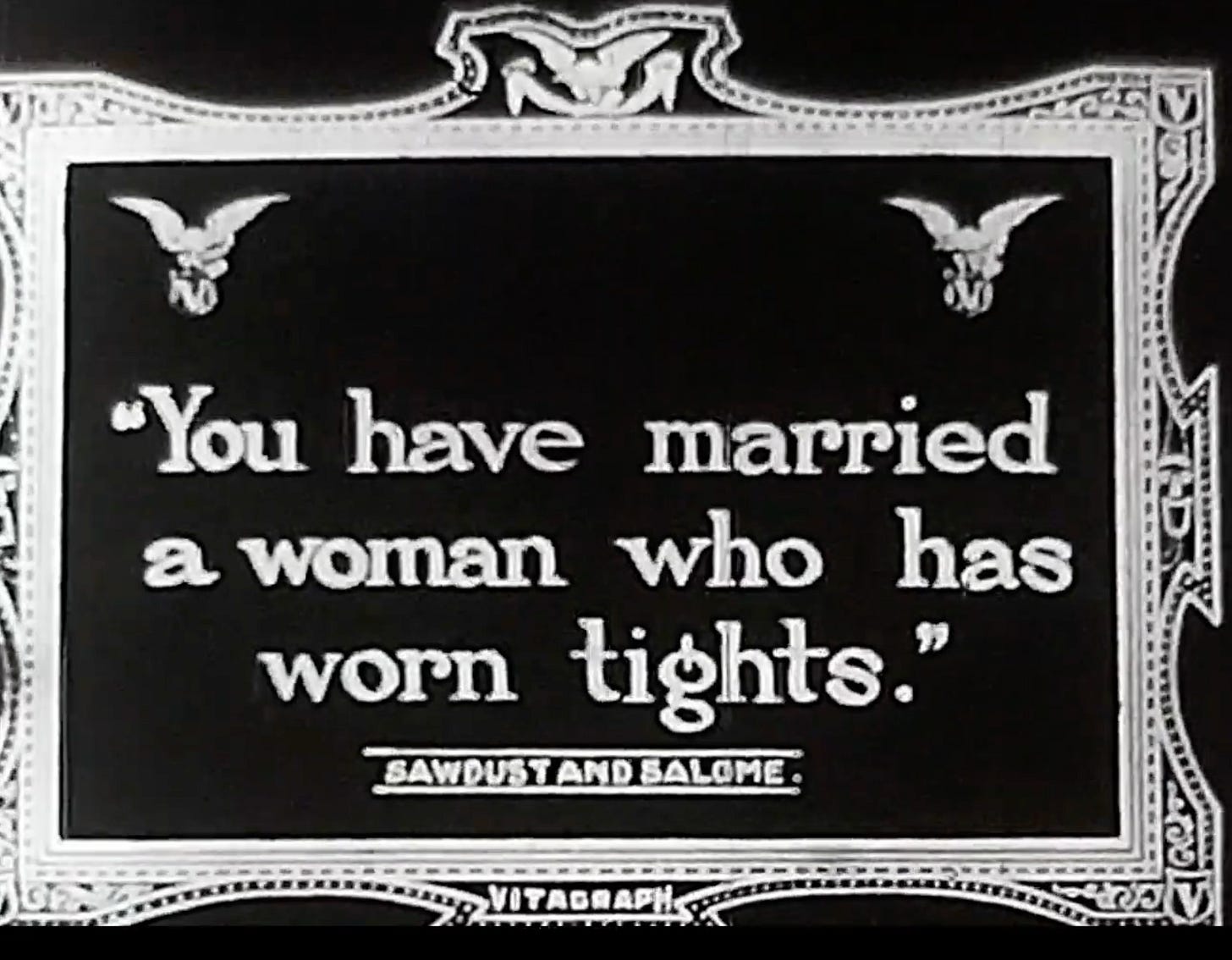

The best moment in the three films came in Sawdust and Salome, when the wealthy son returned home with Talmadge, playing a horse-riding circus performer, as his bride. Upon seeing a picture of her in her circus outfit the parents declared

and immediately dismissed the idea of having her as a daughter-in-law. Imagine what they’d say about today’s standards of dress!

As for the film officially being discussed today, Going Straight is one of Talmadge’s earliest full-length films, made not long after she moved from Vitagraph to Triangle Pictures. Though directed by Chester M. Franklin and Sidney Franklin, the intercuts and parallel scenes smack of D.W. Griffith, who oversaw much what was being produced at Triangle. Some of the closeup shots remind me more than a little bit of Griffith’s work in The Musketeers of Pig Alley, and on a whole, the action sequences flow here in a manner suggesting the expertise of Griffith, so it’s clear he had more than a passing role in the making of this movie.

Were a modern viewer to watch this film without the context of having seen 60+ films made before it, he probably wouldn’t make much of Talmadge’s performance. That’s a testimony to her ability, as that same modern viewer probably would notice many (most?) of the other actresses I’ve seen overreacting and emoting. Talmadge, much like Mary Pickford, Lilian Gish, and some of the other greats of her era, maintains a level of realism on camera that gives her performance an understated and modern appeal.

Talmadge plays Grace, the wife of John Remington, a successful businessman played by Ralph Lewis. They live what seems to be a normal life, but early on we see Grace come across a news clipping that prompts a flashback, during which we learn about the couple’s sordid past. They were once criminals, and belonged to the Higgins Gang.

An exciting action sequence ensues, incredibly well-directed, whether by the Franklin Brothers or D.W. Griffith who’s to say, which includes some intercut closeups that propel the action as builds to a massive fight between cops and robbers. In the end, John and his partner in crime Jimmy Briggs, played by Eugene Pallette looking impossibly young and slender, are captured. Grace escapes.

Back in the present, we learn that John served his time, and has gone straight since leaving jail. Jimmy hasn’t, and when a chance encounter brings him in contact with John, he takes it as an opportunity to extort money from him, lest he turn in Grace. Of course, the money isn’t enough, and soon Jimmy is back to recruit John to pull of “just one last job.” Grace heads to a friend’s house to play cards for the evening, after which she and her children spend the night. Naturally, the house Jimmy has decided to rob is the house where Grace’s friend lives, and calamity ensues. During the robbery, Jimmy heads upstairs to look for jewelry, and finds Grace asleep with one of her children. He attempts to assault her, seriously injuring the child in the process. John shows up in time to protect Grace, and Jimmy flees.

The next day, Jimmy shows up ready to kill John, but John is able to outsmart him, and throws him out a window to his death. Meanwhile, we see that their child, who had been at death’s door, is out of danger and will make a full recovery. John and Grace are once again a happy family.

I feel a lot better versed in the phenomenon that was Norma Talmadge after having watched this film, and the short films from her days at Vitagraph. She has a screen presence that comes through even in the damaged digital print I watched, and avoids the overacting and flailing that so many actresses of her day relied upon to express emotion. Griffith is no doubt in part to thank for that, as he (or the Franklins, if I’m mistaken) gave her closeups for most of her emotional moments, which allowed her to express herself through facial expressions rather than hand gestures and body language.

She shows up several times again on my list of films, as her popularity continued to rise. In 1923, a poll of picture exhibitors named Norma Talmadge the number-one box office star.

I watched this on YouTube, where the print isn’t very good, but the accompanying soundtrack is better than what you usually get with a silent film online.

Next I’m watching The Fireman [1916], directed by Charles Chaplin.

Share this post