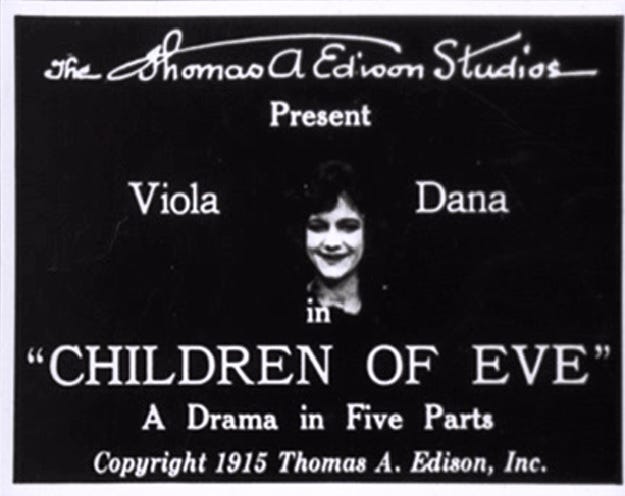

It’s easy to dismiss most of the directors not named D.W. Griffith who were making films in 1915, and for the most part it can be understandable if one does so, but there were a handful of directors doing more than churning out what today would be called “content” at that point in the history of film. Cecil B. DeMille is another big name who was finding his footing in 1915, along with Maurice Tourneur, Raoul Walsh, and Raymond West. Those are the Big Names whose films I came into this project excited to watch, and from whom I expect to see great work. A name I was wholly unfamiliar with is John H. Collins, but after watching Children of Eve I’m ready to add him to that short list of early greats. I’ll see a few more of his films as I make my way through my list, and I’m very curious to see if they are as enjoyable as this one.

Collins directed 15 short films in 1914 and 1915 before switching to feature-length films. Children of Eve was the sixth, and final, feature-length film he directed in 1915, and from what I can tell, it was positively received by critics of the time. His work generally seems to have been praised, and had he gone on to have a longer career, I don’t doubt he’d be better known today. Sadly, he died in the influenza outbreak of 1919, leaving only a small body of surviving work behind. I am entirely convinced that had he survived, his name would be held in the same regard as the aforementioned stars of the silent era.

Collins worked for the Edison Company, which probably hasn’t helped his legacy. Everything I’ve read suggests that Edison was known for churning out average films at a quick pace to feed a growing market for film, and was a company wholly focused on the bottom line. From what I’ve seen of the Edison films, this is true. Based on what I’ve watched, Edison’s 1915 one-reelers are practically indifferentiable from what they were releasing in 1910, which makes Collins’ work all the more noteworthy to me.

Children of Eve is an exception to the Edison formula. It stars Viola Dana, to whom director Collins had been married in 1915, as Fifty-Fifty Mamie, so-named because she always splits the money she makes in dance contests 50/50 with her partner. Before we meet her, we meet her mother, Flossy, a prostitute from New York's East Side. She befriends Henry, a young clerk who lives in a neighboring apartment, who encourages her to reform her life. She does, and they fall in love, but she leaves him because she feels she’ll only be a negative influence on his life. She doesn’t tell him she’s pregnant, and ends up having the baby and dying shortly thereafter, leaving young Mamie with nothing besides a picture by which she can remember her mother.

The basic plot is very similar to what I saw in Rags, but with an extra layer provided by the film’s message about labor reform. Like Rags, and many other films I’ve seen, Children of Eve relies on some very unlikely coincidences to push the plot forward. Apparently audiences at the time were more forgiving of such plot contrivances, although even as I typed that I realized that a great number of modern films also rely on coincidence as a primary plot device, albeit better disguised than it was in the early days of film.

We pick up the story 17 years after Flossy’s death. Mamie is now a party girl, going out dancing with her main squeeze, Bennie the Typ, who besides being a great dancer is a low level criminal. We catch up with Henry, who never recovered from Flossy’s departure, and has turned from being a kind-hearted man to a greedy industrialist. In one of the coincidences I mentioned as being typical for the era, Mamie encounters Henry’s nephew Bert, who prevents her being arrested for shoplifting. He takes a liking to her, and convinces her to give up her wanton lifestyle and find religion.

Mamie starts hanging out at the settlement house where Bert volunteers, and he gradually introduces her to a new, more fulfilling lifestyle. At one point, he grows ill, and Mamie tries to visit him at home. Henry intercepts her, and sends her away, telling her to forget about Bert, explaining that her low societal position will make her nothing but a burden on him— very much the same thing Flossy had told him years ago, only by now he’s become hardened by the world and considers it good advice this time around.

Some of Bert’s activist friends recruit Mamie her to help in their crusade for social justice, and ask her to go undercover as a factory worker to help expose the terrible working conditions therein. Mamie goes to work in Henry’s canning factory, where he is employing children in a workplace that has no fire escape and only one staircase. Naturally, during her day there, the cannery catches fire, many children die and Mamie is fatally injured. The fire was based on a real-life event of the era, the fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in 1911, and Collins pulls no punches in depicting it. We see many dead children lined up in the aftermath. In addition to its stark realism, it is it a well-filmed, and brilliantly edited, sequence, that showcases Collins as a true directing talent.

Mamie is home, dying and Henry visits her, still unaware of who she really is. As far as he knows, she’s just another guttersnipe who was unfortunate enough to die in one of his factories. He’s initially reluctant to have his doctor help Mamie, but when he sees the picture of Flossy on her desk, everything becomes clear to him, and he understands Mamie is his daughter. He implores the doctor to help her, but is rebuffed, being told that money can’t change her situation. Mamie asks for Bert, who arrives in time to see her die. Crushed by all that has happened, Henry’s eyes at last open to what he has become, and he resolves to change his ways, and fight for the welfare of workers and work to put an end to child slavery.

If it sounds grim and a bit heavy-handed, at times it is, but it’s still a powerful piece of filmmaking by a director long forgotten by most. I have three more films directed by John H. Collins on my list, and am looking forward to seeing more from this director whose career ended far too soon.

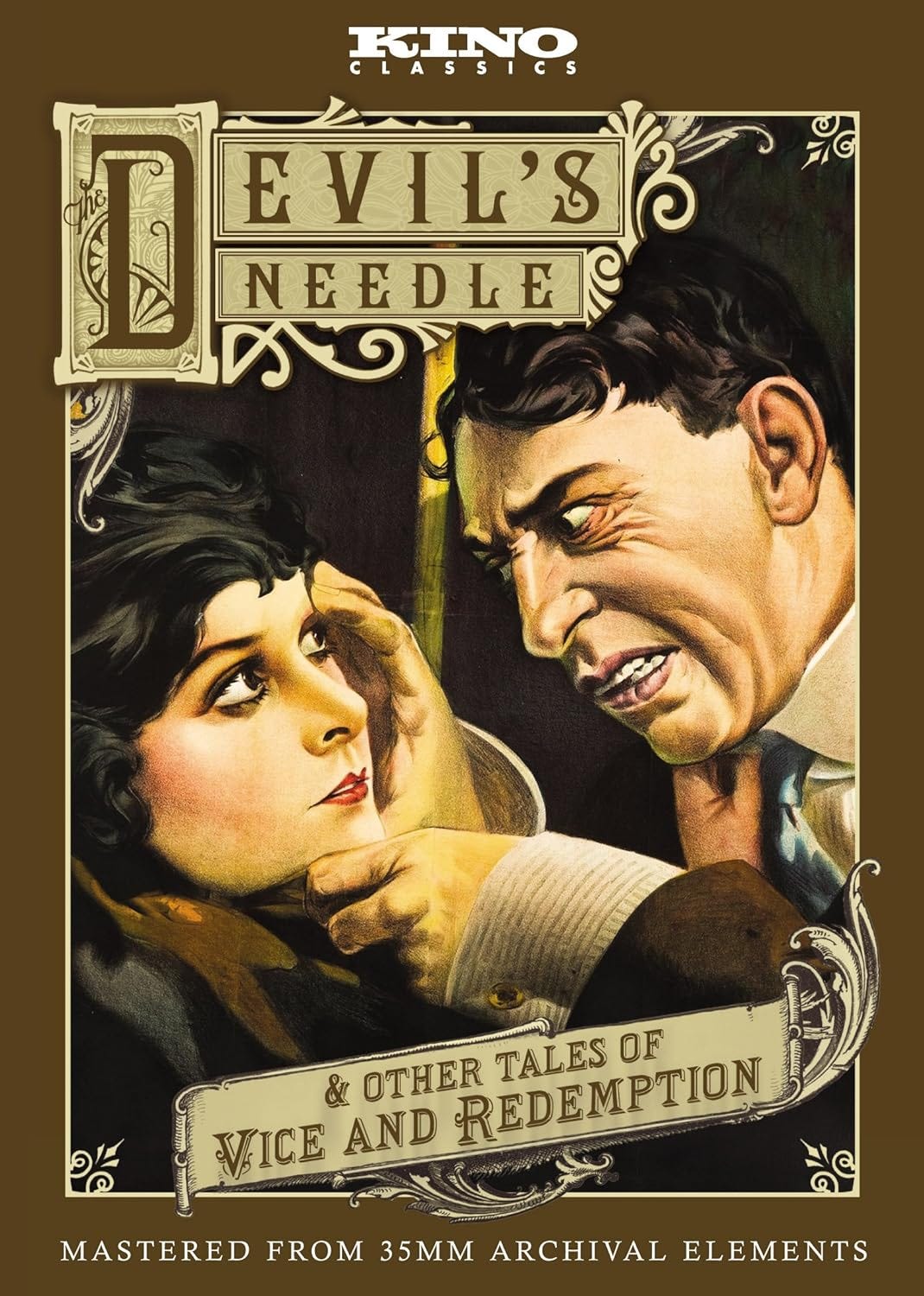

I’ve seen a few DVDs of this for sale online, and am considering adding it to my collection, though it’s sometimes hit or miss with such DVDs. Some are homemade DVDs made from what look like videos copied from YouTube, and others are legit, restored versions made by professional companies. It’s hard to know what I’ll get, but if I do buy one, I’ll report about it. In the meantime, I watched this on YouTube, linked below. It’s an unusual version, with a restored and unrestored version playing side by side. I doubled the image size, and scrolled right to get the full-screen view of the restored version.

I eventually did buy this on DVD. It’s one of three features on the Kino DVD shown below. The Devil’s Needle is on my list of films to watch, so it made sense to pick up a copy knowing I’d also be getting Children of Eve, as well as a third film that won’t be a part of the podcast, but I’ll certainly watch as well. You can click the image if you’d like to buy a copy of your own. Kino always does a great job with their releases, and is one of a handful of brands you can reliably trust to deliver the goods

.

Next I’m watching: A Night in the Show [1915], directed by Charles Chaplin.

Share this post