This is the 40th film I’ve watched as a part of this podcast, and one of just a few that I was truly aware of before beginning. I’ve enjoyed silent films since I was in my twenties, but before starting this project I’d never actively sought them out for home viewing. If I had the chance to see one in a theater, I’d do so, but theaters seem only to show the most well-known silent films, most of which were made towards the end of the silent era. Since I am watching the films chronologically, I’ve so far seen mostly lesser-known movies, so it was interesting to finally watch a film that is still well-known today, and a film I’d long meant to watch.

The film may be most known today simply for being controversial. The picture of the movie’s poster, shown above, starkly illustrates that controversy. And honestly, I knew little about this film other than it is allegedly a well-made, but racist, film, and so I went into it with those preconceived expectations. I have a very different point of view after watching it. I don’t want to delve deeply into the topic of race and racism, and would rather discuss the merits of the film as a film, but it seems impossible to talk about The Birth of a Nation without the topic of race coming up. With that in mind, while the film certainly contains imagery that will startle or disturb most members of a modern audience, the film itself doesn’t put forth a racist message. It’s a fictional drama/romance intermingled with a historical depiction of the South in the years just before, during, and after the Civil War. However, it’s the history told from the Southern point of view, which I think is a large part of the reason it gets branded a racist film.

If I had to sum up the film in a single, short sentence, which is difficult to do for a film that is over 3 hours long— the longest film ever made at the time of its release— I’d say that it is a staunchly anti-war film. The message it hammers home time and time again is that war, no matter how just the cause, is best avoided, and nothing can justify innocent young men being dispatched to battlefields to kill one another on behalf of wealthy and/or powerful individuals who remain safely at home. The film takes its time setting the stage for the war to come, allowing its audience to become invested in the friendships and romances of two families, one from the North and one from the South, before they are torn asunder by the war.

It’s worth noting that World War I was being fought in Europe when this film was being made, and though The Birth of a Nation is ostensibly about the Civil War, there is some very clear subtext that can be read as an admonition for the U.S. to stay out of the war happening in Europe. That warning of course wasn’t heeded, as the U.S. did enter he war a little more than two years after this film was released.

The film captures war in a very stark and realistic manner, and the war scenes are the most harrowing and emotional I’ve ever witnessed in a film. Before this I would have named Saving Private Ryan or Hacksaw Ridge as films whose depictions of war affected me on a visceral, emotional level, but neither come close to the feelings The Birth of a Nation elicited from me during the war sequences.

It’s also worth noting that this film was made 50 years after the end of the Civil War, which would have been as recent and relevant to audiences then as a film about the Vietnam War is now. Many people who had lived through the war would have seen this film, and certainly were involved in its creation, which I believe went a long way towards making its depictions of history so realistic. When The Birth of a Nation came out, Lincoln’s assassination was about as recent a historical moment as Nixon’s resignation is today, so despite feeling like ancient history to us now, the Civil War was an event that many who watched this film had lived through.

Visually the film is far ahead of anything I’ve watched yet. It flows like a modern film, and despite a running time of 3 hours and 13 minutes, it never drags. It starts by introducing two families, the Stoneman family from the North, and the Cameron family from the South. The two Stoneman sons are friends with the three Cameron sons, so the families get together in South Carolina. The Stoneman daughter, Elsie, played by Lillian Gish, doesn’t make the trip. While there, Phil, the oldest of the Stoneman brothers, falls in love with his friend’s sister Margaret. Meanwhile, Ben Cameron sees Elsie’s picture, and falls for her. Not long after this visit, the Civil War breaks out. Suddenly the five young men are fighting in a war, on separate sides. The youngest Stoneman brother is killed in the war, as are two of the Cameron boys. Only Ben and Phil survive. In one of the most powerful moments in the film two of the brothers encounter one another on the battlefield. Both have been mortally wounded, and despite being on opposite sides of the conflict, die as friends in one another’s arms.

The film continues with an account of the post-war chaos in the South, and moves between the historical story, including the assassination of Lincoln, and the fictional story of the two families. Ben and Elsie finally meet, and by the end of the film they are together, and the reconstruction of the South is underway.

The history portion of the film includes the creation of the Ku Klux Klan. This is no doubt the source of most complaints of racism against the film, and also the unfortunate and enduring legacy of the film. The original Klan only existed for about 5 years after the war, and was formed as a resistance movement against opportunistic Northerners who had come to the South seeking power and wealth amidst the ruins of the war. After the film was released, a new Ku Klux Klan was formed— the racist and evil one we all know today. So while criticism of the film itself as racist is certainly misguided, it’s fair to say that its anti-war/anti-violence message backfired, and it instead inspired an unfortunate amount of hatred in its wake.

Despite the controversy and backlash it sparked, the film is remarkable in purely cinematic terms. It’s so far beyond anything that came before it that it almost feels like the style and language of the modern film was birthed with The Birth of a Nation. It is hands down a masterpiece. It is both technically astounding and entertaining.

It was also a stunning box office success. Accurate records weren’t kept at that time, so we don’t know exactly how much it made, but in today’s dollars it made a minimum of $1.5 billion, and most estimate it brought in closer to $2 billion in 2023 dollars. Audiences sold out every show, day after day, for special showings in New York for which tickets cost $64 apiece in today’s dollars. However much it made, it was one the most financially successful films of all time, despite the controversy that surrounded it from its release.

I watched this on a blu-ray, linked to the picture below. It contains a number of special features, including two versions of the film and a number of D.W. Griffith’s early short films.

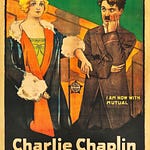

Next I’m watching: The Tramp [1915], directed by Charles Chaplin.

Share this post