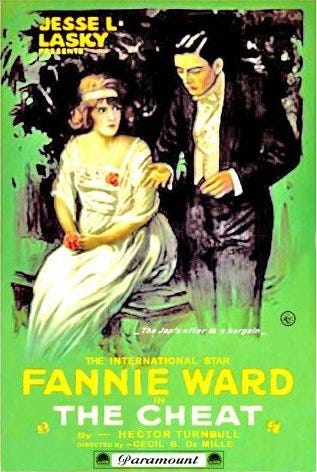

The Cheat is the 23rd film Cecil B. DeMille directed. That seems like a long career, but those films were released over a span of 22 months, meaning he had less than two years as a director under his belt when he made this movie. Despite being so new to the art, his talent is apparent. This is a beautifully shot film, and includes the most effective usage of lighting and shadow that I’ve seen thus far.

The story opens with Richard, played by Jack Dean, sinking his entire fortune into an investment. He informs his wife, Edith, played by Dean’s real-life wife Fannie Ward, that she must temporarily curb her spending. She’s been spending a small fortune on clothing, and for a fund raiser for Belgian war orphans she’s helping organize. She’s the treasurer of the Red Cross chapter that’s putting on the fundraiser, and is entrusted with the $10,000 they’ve raised. She promptly gives it to a friend who promises he can double it overnight with an investment he insists is better than the risky one her husband has made. Naturally, he shows up the next day to tell her that the investment didn’t pan out, and the money is gone. Now she’s in a pickle! She has less than a day to come up with $10,000 to give the Red Cross.

She turns to her best friend, Haka, a Burmese ivory merchant with whom she spends most of her free time. He offers her the money, in exchange for a night together in bed. She reluctantly agrees, knowing the alternative is jail for embezzling the funds. When she returns home, her husband tells her his investment has panned out and they are rich beyond their wildest dreams. She asks him for $10,000 to cover a loss in a game of bridge, so he writes her a check. When she delivers it to Haka that evening, he refuses, telling her she needs to stick to their original deal. She tries to flee, he locks her in the room. There’s a struggle, and at one point Haka grabs her, and brands her shoulder with the red-hot brand he uses on his ivory. Desperate, she finds Haka’s gun and shoots him.

As this is happening, Richard shows up. He was suspicious about the alleged bridge debt, and has come to find his wife. Assessing the situation, he sends his wife away and when the police come, he tells them he shot Haka. Haka doesn’t dispute this, likely seeing a way to get his romantic rival, and Edith’s protector and source of income, out of the picture. In the subsequent trial, he maintains his guilt, but won’t offer a reason for shooting Haka. When he’s convicted, Edith finally bursts forth and tells the truth. When she shows the brand on her shoulder as proof, the judge dismisses the case, and Richard and Edith leave together.

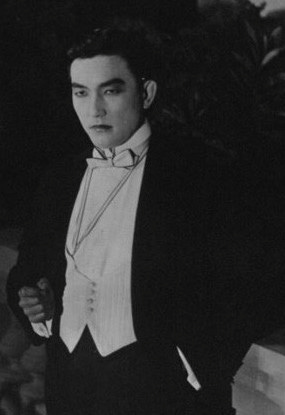

When it was first released, the villain was a Japanese ivory merchant, which lead to protests by Japanese-Americans, so upon its rerelease in 1918, DeMille changed him from Japanese to Burmese. Nationality aside, the character was played with extraordinary aplomb by the Japanese actor Sessue Hayakawa, for whom the role became his breakthrough to stardom. He became Hollywood’s first Asian matinee idol, and the first non-white international movie star. Stephen Gong, the executive director of San Francisco's Center for Asian-American Media, writes “It [the film] caused a sensation. The idea of the rape fantasy, forbidden fruit, all those taboos of race and sex – it made him a movie star. And his most rabid fan base was White women.”

Up for debate is whether the film is racist or not. Some will of course say it is, as the villain is played by an Asian actor, but I’d counter that his race is never a focal point of the film. It’s more that he happens to be a Burmese merchant. He could have been Turkish or Belgian, or even American. Moreover, he is clearly an accepted member of the upper class in the film. No one objects to his presence, or treats him any differently due to his nationality. So at least to me, it seems as nothing more than a villain being played by a Japanese actor.

More noticeable to me than anyone’s race is deMille’s pioneering use of what’s known as Rembrandt lighting. In numerous scenes, an actor’s face would be partly lit, partly in shadow. Hayakawa is the prime beneficiary of this technique, but there are many such scenes in the film. It works extremely well, and many lengthy shots from an immobile camera are augmented by this kind of lighting.

I watched this on a DVD, which includes a second Cecil B. DeMille film, Manslaughter, which I’ll watch later in the chronology. You can purchase your own copy by clicking on the picture below. On the advice of several people, I have created an Amazon Associates account, so if you do buy something from Amazon using my link, I may receive a few pennies.

The Cheat is also available on Amazon Prime, where it is available free to Prime members. I took a peek, and the quality of the film is solid, if not great, and the brilliance of DeMille, and cinematographer Alvin Wyckoff, is clearly visible. I still recommend you buy the DVD.

Next I’m watching After Death [1915], directed by Yevgeny Bauer.

Share this post