directed by Raoul Walsh

I only know Raoul Walsh from a few gangster pictures he made in the late ‘30s and early ‘40s, so I was curious to see some of his earlier work. Quite a few films he’s directed are on my list— 17 I believe— and The Regeneration is the first one to show up in the chronology. Despite being made in 1915, it stands up to his later work, and honestly, is as good as any modern film. Sure, it’s dated in some ways, but that’s the nature of all art, right? Any work of art is a product of its time, but it is the timeless qualities of the piece that allow it to stand out, and The Regeneration is timeless in the ways that matter.

Having extolled its timelessness, I’m going to start by praising this film for one of the ways it is most dated. The Regeneration was filmed almost entirely on location in New York’s Bowery. It’s really only through films like this that we can get a real glimpse into how that neighborhood looked back then. Sure, we can read all about it in myriad books, but nothing beats seeing the real tenements, streets, cars, and people on film. Just seeing the spider’s web of clotheslines strung between the buildings is a powerful reminder of what our cities once were, so even without a for its time spectacular stunt of a man climbing between buildings on one of those lines, the scene was fantastic to behold.

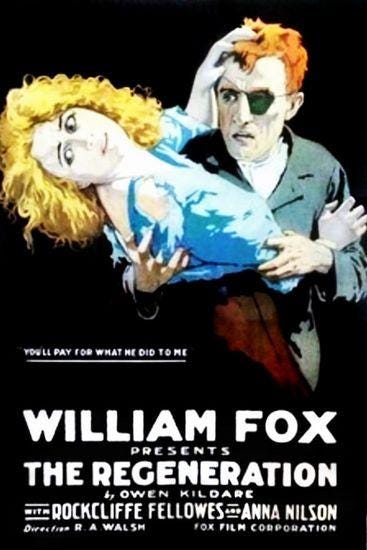

Part gangster movie, part morality play, The Regeneration traces the life of Owen, played as an adult by Rockliffe Fellows. We meet him first as a child, an orphan, taken in by abusive parents who use him as a servant. We see through his eyes as his parents drink and fight. We also see what apparently was a normal thing in 1915: Owen is sent by his stepfather to a nearby saloon with a coin and a bucket. He slips both under the swinging doors to the bartender, who moments later slides the bucket, now full of beer, back out, which Owen brings to his father, but only after sneaking a sip for himself. Later in the film we witness a den of gangsters passing around a similar (the same prop?) bucket of beer around. I take it to mean that going to a bar to fill a pail with beer wasn’t unusual back then.

Anyway, we rejoin Owen in his teens. He’s now living in the streets, running with a gang. He isn’t all bad, however. When he witnesses some bullies pushing around a crippled teen, he intervenes, and beats up the bullies. He’s still a good guy at heart, this Owen. Another time jump brings us to the present day, and we learn that Owen, now 25, is the boss of the toughest gang in the Bowery. Meanwhile, across town, we see the wealthy district attorney, played by Carl Harbaugh, dining with some of his rich friends. The conversation turns to gangsters, and one guest, Marie, Anna Q. Nilsson, exclaims that she’d love to see a gangster in the flesh. Ames tells her he knows just the place, and he leads a few of them to a saloon in the Bowery.

Apparently, the poors don’t take kindly to being gawked at by rich folk, and a scuffle breaks out. Owen is observing this when Marie catches his eye, and in a great bit of silent acting, implores him to intervene, which he does. He saves Ames, and escorts the party out to their car. As they part ways, we can see that Owen and Marie have taken an interest in one another.

Marie’s interest runs deeper than just her curiosity about Owen, as she was struck by a speech from a reform advocate she overheard as she was leaving the slums. She decides to devote her heretofore empty life to helping the unfortunate denizens of the Bowery, and takes up volunteering at a Settlement House therein. Owen notices her, and, though hesitant at first, keeps an eye on her from afar before finally being won over when he’s recruited to help rescue a baby from an abusive father. Flashing back to his own unhappy childhood, Owen realizes that Marie’s cause is worthwhile, and, to the shock of his gang, leaves his role as head gangster and starts learning to read and write at the Settlement.

The story takes a darker turn when Skinny, a much more brutal gangster, and Owen’s replacement as leader, stabs a policeman. He begs Owen to hide him at the Settlement, and though Owen at first refuses, he acquiesces when reminded of a time when Skinny had lied to the police to save Owen. The subterfuge works when the police come, but Marie, and a visiting Ames, find out that Skinny is hiding, and admonish Owen. Ames taunts him, telling him that Marie, who has fled to her room in disappointment, will never love him after his error. Surprisingly, she comes out with a redoubled devotion to Owen, determined to help him stay straight. Owen, ashamed, flees, and the audience can’t help but wonder if he’s out to get Skinny.

He’s not. He sends a note to Skinny saying that they’re even now, and to never bother him again, and heads to a church. There, he consults a priest, who also tells him that he’s a good guy, and he can’t stray from his righteous path simply because of one lapse in judgment.

Marie, meanwhile, does think Owen is after Skinny, or perhaps has rejoined his gang, for she heads to the gang’s clubhouse to find him. There, she’s duped by Skinny into following him into an empty bedroom, where he attempts to assault her. She barricades herself in a closet. While this is happening, Marie’s assistant, the crippled youth Owen had helped years ago, runs to let Owen know about Marie’s predicament. Owen arrives in time to chase Skinny away, who shoots at Owen as he escapes. The shot misses Owen, but mortally wounds Marie. On her deathbed, she implores Owen not to avenge her, shown in a striking and clever manner. Rather than a title card, she points towards a scroll that is superimposed onto the screen, and contains the verse from the Book of Romans, “Vengeance is mine, saith the Lord.” That would be out of place, and perhaps even comical, in a modern film, but in the context of the scene, and in an era where all films were silent, it’s clever and meaningful.

Skinny does received his comeuppances, though at the hands of the crippled youth, played by an unnamed actor who I wish I knew more about. He is a standout as the hunchbacked character in this film, and, to Walsh’s credit, is never singled out as a freak or anything special. He sees Skinny trying to avoid the police by climbing from one building to another on a clothesline (the stunt I alluded to earlier), and shoots at him. It isn’t clear if he hits him, or if it’s simply the surprise of the shot, but Skinny falls to his death.

Besides keeping Owen on the right path, his choice not to avenge Marie’s death adds an extra level of emotional weight to her murder. Had he been on the fence, and only decided to remain moral due to her death, it would feel like more of a plot contrivance, but it’s clear that he was already determined to do right before she was killed. Her death is simply a tragedy, and not a necessity of plot.

I really enjoyed this film. Intellectually, it’s certainly on par with what Griffith was doing at the time, though of course it is visually less innovative. This could well be in large part due to the budget Griffith had, as well as the scope of the stories he was telling. On the topic of Griffith, here’s an interesting side note: while this is the first film I’ve watched for this project that was directed by Raoul Walsh, it isn’t the first time I’ve seen him. He had a small role in The Birth of a Nation, in which he played John Wilkes Booth. He was also an assistant director, and part of the editing team on that film, and he clearly learned a lot from Griffith.

I’ve reached a point in cinematic history where there is a lot more structure to the filmmaking process. In many ways, 1915 seems to be the beginning of the modern era of film. It isn’t as if The Birth of a Nation instantly revolutionized film, and everything that came after was different, but it’s clear that moviemaking was moving away from the independent, and often haphazard, methods of its early days, and become far more organized, and supervised. The studio system wasn’t fully in place, but I’m beginning to see its roots, and films, at least the better ones, are now being made by coherent teams of people as opposed to one guy with a camera. From here on out, I think it’s going to be important for me to pay attention to more than just the director and actors in a film. Writers, cinematographers, assistant directors, producers, and other people are starting to play key roles in film by 1915, and it’s becoming interesting to track their progress.

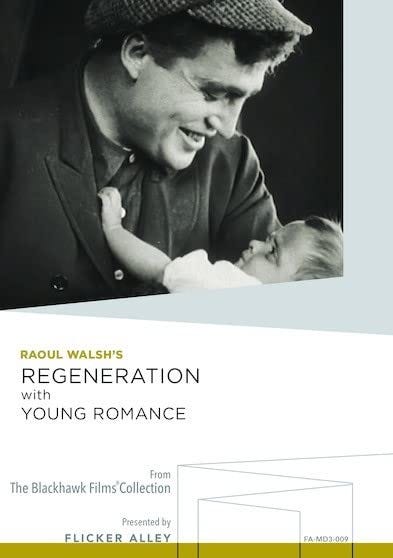

I watched this on a DVD from the Flicker Alley collection, and I highly recommend you buy and watch it. It also contains a film I watched previously for this podcast, Young Romance. And I should add— I don’t make anything if you buy these blu-rays and DVDs. I link these to help you find he films. You can click the picture below if you want to buy this great film.

Next I’m watching: Pool Sharks [1915], directed by Edwin Middleton.

Share this post